Who can you trust?

In our previous article, we discussed how governments and corporations have been spying on their citizens and users, and circumventing end-to-end encryption in more ways than we are all aware of. Whether it’s the NSA, the FBI, or Facebook recording audio and video, the public often only finds out when they get caught. You can read more here:

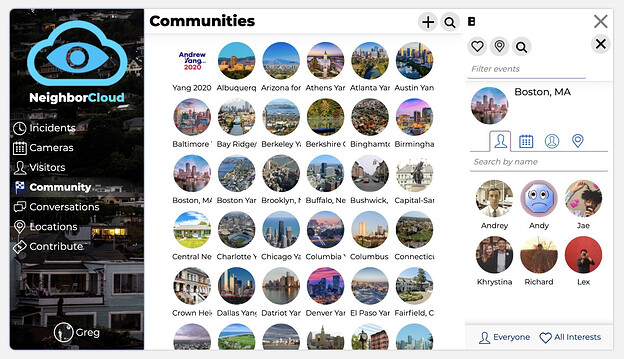

Open source software is essential for people to actually guarantee that the code they’re running is doing what they expect. At Qbix, we are developing ways for regular people to easily verify the integrity of these guarantees, and ensure them to a great degree, without having to trust large corporations. Qbix Platform is perhaps one of the most advanced open source social community platforms in the world, and we’re soon going to be rolling it out to our millions of users.

Just because large states and corporations choose the “easy route” of spying on their citizens and users doesn’t mean there aren’t real concerns that communities have about violent crimes and people harming one another. Can a compromise be struck between Privacy and Accountability?

Privacy and Accountability

Qbix can be used inside organizations that employ people, and have to comply with regulations. Many such organizations, including corporations, would like to record conversations to see what happened. Such logs can aid in investigations. Transparency is very desirable when it comes to people officially working for a community. Body cameras for on-duty cops is a great example, as is C-SPAN. But much more broadly, we as a society would benefit if we required our politicians to make deals in public.

However, there are lots of private interactions between people – on video and chat – which don’t occur in the context of serving the public or an employer. These include romantic and sexual encounters. On the one hand, when someone is harmed (for example cases of rape or assault), having access to video of what occurred would be very useful in solving the actual crime. On the other hand, the brute-force approach would be very intrusive and unacceptable for privacy: putting cameras in every dorm room on a campus for the purposes of recording all movement. Can there be a middle ground? It turns out that, yes, there can!

Balancing Privacy vs the Public Interest

Our CEO, Greg Magarshak, has been writing about these issues since 2012 and 2014. As with most complex public issues, there are good points on many sides, and sometimes the solutions are found not from following the loudest voices or the strongest hammer but in the most nuanced and well-architected technology, deployed bottom-up by the people on the ground.

On the one hand, end-to-end encryption can be a band-aid masking larger societal problems. If peaceful people are reduced to sneaking around, the problem is upstream: they need to fix their government and corporations, and improve the organizing principles on which their society is based. On the other hand, end-to-end encryption can be a very useful piece in a larger solution in which due process can be followed and crimes can be solved in cases where it would otherwise be very hard to find out what’s going on.

We’ve already spoken about the need to trust the devices and software we use every day. So one part of the solution (which is not the norm today) is open source software deployed by end-users and communities. How should such software employ encryption?

Provably Encrypted Surveillance

Sexual assault is the most commonly reported crime on college campuses, yet it’s hard to determine what happened, leading more and more jurisdictions to pass yes means yes laws. These laws typically shift the pendulum from women to men in terms of burden of proof, and challenge the widespread presumption that the accused is innocent until proven guilty. But proof is often hard to come by in either direction, so one or the other party often ends up cheated of a just outcome.

As with most complex public issues, there are multiple nuanced solutions that can take advantage of new technology. Imagine if the entire college campus was outfitted with cameras, including in bathrooms and bedrooms of dormitories. Except all these cameras would be specifically built to encrypt the video on-board the camera, before the video is sent out to be stored. Moreover, the encryption key would change every minute on every camera, so the stored clips would each have a unique decryption key.

Now, decryption of any given cameras + time intervals would require several things to happen:

- Someone would have to bring a case to the local authorities

- An investigation would be launched, to gather as much information as possible (interrogating witnesses, etc.)

- A court case, or arbitration proceeding would be convened, so the suspect would be able to face their accuser in court (due process)

- During these proceedings, specific minutes of video from specific cameras would be subpoenaed. This would provide some of the necessary decryption keys to decrypt those specific minutes, and nothing else.

- The video could be the missing piece for everyone involved in the arbitration proceeding, for a verdict assigning blame and consequences to one party or another, or some combination of the two. In any case, the dispute would be resolved based on what actually happened.

Who Watches the Watchers?

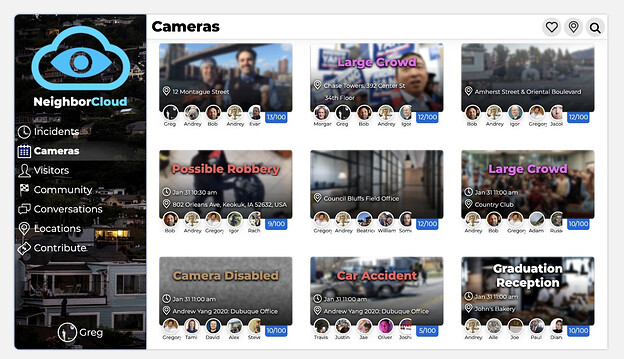

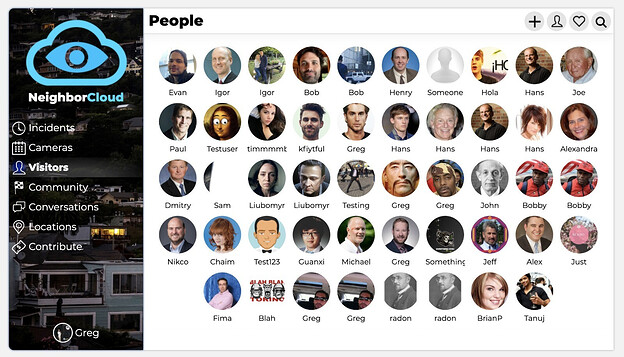

Imagine a neighborhood association whose members install cameras all around their homes, front yards, and roads. The cameras can capture license plates, and even run on-board AI to flag certain problematic minutes of footage (e.g. domestic violence). None of the video would be sent unencrypted, but certain things would be flagged for investigation.

The difference between the system being described here, and CSAM scanning like what Apple made or what what EU regulators propose to mandate, is primarily in the accountability for those who decrypt the data.

Whether it’s video or text, each small part is encrypted with a different key. To decrypt it, multiple parties need to come together and combine their keys, all the while creating an audit log of why they are accessing this or that portion. A valid reason might be “the AI flagged a possible armed robbery in progress”, or “a court has subpoenaed these couple hours where an assault is alleged to have occurred.” The decryption will require an audit log to be created, so the watchers and the whole system will have accountability as to why it is decrypting certain video. Global limits can also be placed on the system, to help prevent abuse and collusion and focus everyone on solving real crimes.

At Qbix, we have already implemented optional WebRTC extensions like Facial Recognition and Eye Tracking to make sure students are paying attention. In those extensions, the student might be required to turn on their camera by the teacher (in distance learning scenarios) but their video is not sent anywhere. It’s just analyzed locally, and only a yes/no signal is sent to the teacher. That way the teacher can know know whether the student is present and paying attention, without having to see them, how they look, or their surroundings. The system being described here simply builds on what we already have, but with encryption and open source hardware.

Preventing Crimes and Disputes

Finally, we should point out that many disputes are already resolved in the financial system. Auto accidents are solved by insurance companies. Payment disputes are solved by credit card issuers and banks. They see thousands of cases a day and they have developed frameworks that solve things without violence.

Increasingly, as more people get access to UBI and education online, there might be less crimes overall. Visitors to a neighborhood would identify themselves, and a lot of damage they cause could be adjudicated and resolved via online mediators and insurance. Amazon Go even pioneered stores where most shoplifting or property destruction would simply be charged to the user’s account, preventing a lot of it in the first place.

But one could go further, to actually prevent many crimes and disputes. In 2017, we spun out a company called Intercoin to build Web3 applications for communities. Whether it’s DeFi or Voting, communities can increasingly govern themselves without violence. On the internet, there is no physical violence, and many disputes can be resolved through agreed-upon mediators. With Web3, no one can take on debts they can’t pay, and there is no need for credit bureaus, as all participants can see the information on-chain and agree to what will happen. It is a far better system than something like this: